Abolitionist Pedagogy, Abolitionist Poetics

an essay contributed by Lindsay Reckson

art don’t work

for abolition.

art works for

bosses, like you

and me. if “let’s

abolish art” sounds

too close to “let’s

abolish you and

me,” it’s ‘cause it

is. I love art and

I love you, too,

and this is a love

song, so it’s got

to be too close.

Fred Moten, “the abolition of art, the abolition of freedom, the abolition of you and me.”[i]

1. We begin the class with Audre Lorde because Emma reminds me that it’s not possible to begin anywhere else.[ii] “Poetry is not a luxury.”[iii] We could spend the entire semester on what this means, and especially what it means in the space of a liberal arts classroom, in a course on poetry written in carceral spaces, from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, to the Topaz War Relocation Center in central Utah, to the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia, to the Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp—“school,” “center,” and “camp” here are all euphemisms—as well as prisons like San Quentin and Attica and the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, Texas.

Our classroom is in the renovated Visual Culture Arts and Media (or VCAM) building on Haverford College’s campus, an architecture design award-winning space with high tech projection and lighting. There’s a video editing suite below us, a studio for artists-in-residence across the hall, a maker space, gallery spaces, a screening room, and a communal kitchen downstairs where someone is often making a communal meal.

In this classroom, I tell my students about Lorde publishing the essay, originally titled “Poems are Not Luxuries,” in the LA-based feminist journal Chrysalis in 1977, where she also served as the poetry editor. In the essay, Lorde signals that what she means by poetry is “not the sterile word play that, too often, the white fathers distorted the word poetry to mean.” On the contrary, for Lorde, “poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so that it can be thought.”

We talk about the performative force of Lorde’s address, her calling in of a transformative “we” and “us”: “The white fathers told us, ‘I think therefore I am,’ and the black mothers in each of us—the poets—whisper in our dreams, ‘I feel therefore I can be free.’ Poetry coins the language to express and charter this revolutionary awareness and demand—the implementation of that freedom.”[iv] I tell my students that I want to hold on to philosopher Sylvia Wynter’s critique of the “we” as a violently universalizing gesture; the white patriarchal “we” not only assumes the exclusion of Black and indigenous peoples from the concept but also underwrites the genocidal projects of colonialism and enslavement.[v] In contrast, Lorde’s “we” is both specific and expansive, a Black feminist collectivity that refuses to be bound by the logic of particularity.

Image description: The cover image of Chrysalis: A Magazine of Woman’s Culture (Vol. 3, 1977) showing a drawing of hand holding a small box, with a winged insect emerging out of it. The contents—including Audre Lorde’s “Poems Are Not Luxuries”—are listed in a column on the left-hand side of the page.

Poetry is not a luxury for the colonized, the enslaved, the exploited, the silenced. It is not a luxury for the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated poets, artists, activists, and intellectuals we’ll be reading and talking to over the course of the semester. But is it a luxury for “us,” the “us” of the liberal arts classroom, with our access to technology, to the communal kitchen, to the intellectual property of people in prison? The classroom is a space we can recognize; puncture; try to crack open; try to share; it’s a space from which we can try to move resources; a space filled with all kinds of students about whom I refuse to generalize; but insofar as it belongs to the institution it is also a colonial and exclusionary space.

What can we do in this space that is not in the service of the “perpetual institution”? (a phrase that circulates through conversations at Haverford about endowments and fundraising initiatives and budgetary restrictions). How do we use this space in the service of something else?

2. Emma (who reminded me to start with Lorde) is a friend and a student activist. Throughout the semester she will fervently cite Joy James on the political economy of social justice and the airbrushing of revolution.[vi] As we talk about the transformative revolutions of metaphor—its tropism, or turning of something into something else—Emma will resist metaphor in ways that I find deeply helpful. I’ll ask the class to grapple with Dr. James’s critique of academic abolitionism, in order to get clear about our work, to get clear about what we are and are not doing.[vii] Though to be honest I don’t always myself feel very clear about what it means to be in the liberal arts classroom these days, or maybe just about how to be reading poetry in the classroom.

In a riff on scholar and poet Fred Moten, I want to ask: who does poetry work for? Does it work for the bosses, like you and me? Are we the bosses or do we work for them? Is this a love song? (I ask that question with bell hooks, June Jordan, Joy James, others who have theorized transgressive teaching and radical love within and beyond institutions).[viii]

3. In his essay “On Poetry” for The Sentences That Create Us, Luis Rodriguez signals a radical tradition of poetics that exceed sterile word play: “As most people know,” he writes, “there’s ‘poetry’ in all manner of writing. There’s poetry in how one comports oneself, the way one strides, or dances. Poetry means movement with such grace, rhythm, and poise that one who observes is aesthetically held, intoxicated perhaps, by the compelling relationship of the parts to the whole. Poetry as a literary genre is where language, imagery, ideas, and emotions are the movements that compose the dance…Poetry is how words and thoughts swim expertly and effectively in a sea, even stormy, of syllables, sentences, and senses.”[ix]

We could spend the entire semester on what it means to be “aesthetically held” by a poem, and whether this holding could operate as a challenge to that other holding, the carceral hold, the cell.

The first poem we read together—a poem that indeed we will hold to for the rest of the

semester—is Etheridge Knight’s “The Idea of Ancestry,” a poem that refuses

techniques of family separation that have been central not only to the prison-industrial

complex but also to racial capitalism and the US state since its inception:

Taped to the walls of my cell are 47 pictures: 47 black

faces: my father, mother, grandmothers (1 dead), grand-

fathers (both dead), brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts,

cousins (1st & 2nd), nieces, and nephews. They stare

across the space at me sprawling on my bunk. I know

their dark eyes, they know mine. I know their style,

they know mine. I am all of them, they are all of me;

they are farmers, I am a thief, I am me, they are thee.[x]

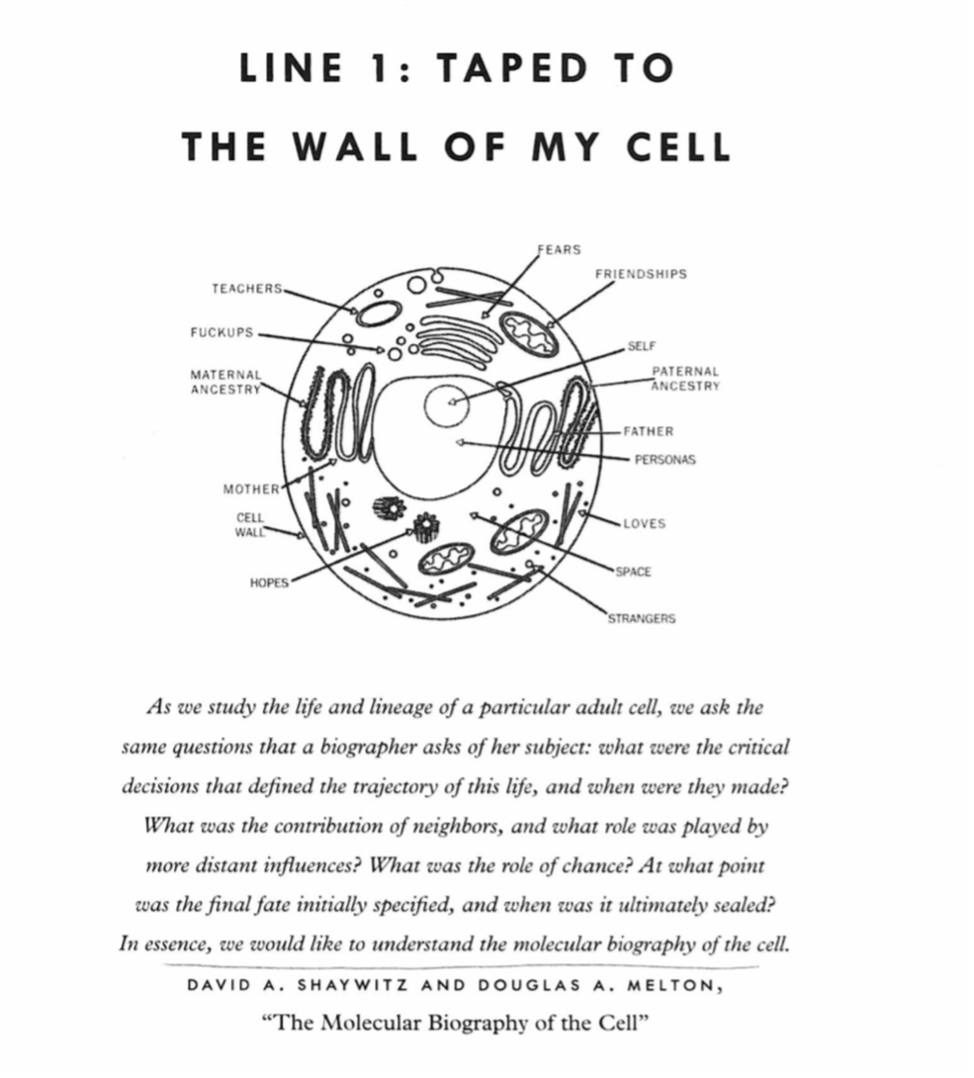

This is a poem about distance and nearness, about knowing and being known through others, about collective Black being. It resists the surveillance regimes of the carceral state in favor of a more intimate exchange of looks, a look that demands something of the poet, that owes something, not to the state but to the people who made and make him. We read the poem alongside poet and artist Terrance Hayes’s To Float in the Space Between, an extended meditation on Knight and poetic influence. We look at Hayes’s reworking of Knight’s “cell” to include friendships, fears, fuckups, teachers, strangers, hopes, personas. As one student observes, if Knight brings his family into the cell, Hayes brings the cell inside of us, the biological metaphor turned on its side, or maybe inside out. Each of us grappling with the violence we inherit, the violence we perpetrate. What does a cell hold?

And maybe: what would abolition at the cellular level feel like? This is a question you can ask in poetry. It is not a question that reveals itself under the microscope.

Image description: A hand-drawn diagram of a human cell, with arrows pointing to components of the cell that indicate “teachers,” “fuckups,” “hopes,” “fears,” “friendships,” “loves,” and “strangers” along with “cell wall,” “maternal ancestry,” “paternal ancestry,” and other components. Below the drawing is an excerpt from David A. Shaywitz and Douglas A. Melton’s “The Molecular Biography of the Cell.” Image source: Terrance Hayes, To Float in the Space Between.[xi]

4. We’re about to do a workshop on “Revisioning Justice” with Felix and Ray, but in this high-tech space we don’t have enough colored markers for each group. “Revisioning Justice” is a workshop developed by Let’s Circle Up, a restorative justice group co-founded by Felix Rosado and Charles Boyd at SCI Graterford (a prison located about 45 minutes northwest of Haverford which closed in 2018 and was replaced by SCI Phoenix). In the workshop, we look at an image of Lady Justice—blindfolded, scales in one hand, sword in another—and talk about what’s powerful and what’s potentially limiting in this image. Then we draw and present our own visions of justice. In an effort to make it work, I suggest some students can use their own pens and pencils to draw. Felix and Ray politely but firmly decline, reminding me that if envisioning is a political act, everyone should get the same tools.[xii]

Image description: an underwater ecology of justice made by students in “Poetics of Abolition” at Haveford College, Spring 2023.

Image description: A Hydra tree of abolition made by students in “Poetics of Abolition” at Haveford College, Spring 2023.

5. In his meditation on the radical redaction of language and information at Guantanamo, poet Jordan Scott asks: “Where can the poet witness if no language survives? If nothing remains?” As the 2007 volume Poems from Guantanamo suggests, poetry lives at Guantanamo, though it lives under constant surveillance; poems are interrogated for their content, for their political “allusions.” As the first outside poet granted limited access to Gitmo, Scott asks about the opacity of poetry—including heavily redacted poetry—as a resistance to state power. He describes being caught under-supervised while taking ambient sound recordings at Camp X-Ray:

My PA escort had not asked for permission to visit Camp X-Ray at night. This was cause for alarm, and brought innumerable guards to the front gates of the camp. Eventually, a member of the Navy Military Police defused the situation when he asked my PA what I was doing at Camp X-Ray at night. The PA answered, “He’s taking ambient sound recordings for a poem, sir.” Perplexed, the Navy MP looked directly at me and said, “A poem?” “Yes,” I replied. He then radioed his superior:

Sir. Yes. Camp X-Ray, sir. A poem, sir. A poem. A poem. Yes. Ambient sound for a poem. Sir. I’m not sure. Yessir. A poem, sir. Yes. Ambient. Sir. Yes.

I was then let go.

Can poetry, as Peter Gizzi once claimed in an interview, be a “mystery in the face of violence”?[xiii]

Image description: Endless squares of cement beneath a blue sky with wispy clouds. Image credit: Jordan Scott, via Lanterns at Guantanamo.

All semester I’m asking this question. Can poetry be a mystery in the face of state violence? Can we learn to read it this way? Can we not interrogate the poem the way I, a literary scholar, was trained to interrogate it through close reading? Instead can reading it be a practice of care? When you love someone, I remind my students, you learn their details. You pay attention to them. It’s a real question: can we learn to read the way that we love? (And conversely, can we learn to love the way we read?) “I love art and I love you, too, and this is a love song, so it’s got to be too close.” Could we read the work of incarcerated poets this way?

6. Building on Rodriguez’s definition of poetry as movement, we talk about the historical role of poetry in movement building: at Attica, before and after the uprising. At Angel Island, where poetry written on the walls helped Chinese immigrants both sustain and organize themselves. In American concentration camps during WW2, where incarcerated Japanese Americans published poems in camp newsletters alongside critical information and survival guides. In the Freedom Schools, where reading poetry was a crucial form of black study, an enactment of what literary scholar Kevin Quashie calls “black aliveness” in the face of a necropolitical anti-black state.[xiv] We talk about why Assata Shakur begins her autobiography Assata with her poem “An Affirmation,” before describing her near-murder by police on the New Jersey turnpike. “An Affirmation” ends with the lines:

I believe in living.

I believe in birth.

I believe in the sweat of love

and in the fire of truth.

And I believe that a lost ship

Steered by tired, seasick sailors,

Can still be guided home to port.[xv]

As a class we are critical of how abolitionist “imagining” has been co-opted by institutions (like our own) that have no interest in implementing prison abolition; still, we read texts in which imagining is, indeed, a radical act. Shakur describes meeting a woman named Eva at the Middlesex County Workhouse:

“My first encounter with Eva was when she came over to the bars and sat down outside my cell and told me she could astro-travel. She called it something like astro-space projection. ‘I can go anywhere I want to, whenever I want to,’ she told me. ‘I’ve just come from Jupiter.’ … ‘Can you show me how to project myself the hell out of here?’ ‘Oh that’s easy,’ she said, ‘I do that all the time. As a matter of fact, I’m not here now.’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘that’s not good enough. I want to project my mind and my body out of here.’ ‘You’ll still be in jail wherever you go,’ Eva said.”[xvi]

Assata concedes the point—the anti-black carceral state is ubiquitous—but says she would like to exchange the maximum security of the prison for the minimal security of the street. We talk about how Eva’s astro-space projection is a Black feminist futurist abolitionism that refuses the boundaries of the carceral state even as it recognizes that abolition has many times, many spaces, many fronts.

7. I tell Rickey about teaching this moment in Assata. Rickey sends me a poem that describes love as a shared space; we talk about the poem itself as a shared space. I send him some lines from James Baldwin (“love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within”); he sends me back lines from bell hooks.[xvii] This is before I’ve met him in person, straining to hear his voice which sounds so far away through the phone though we are inches apart, smiling at each other through the thick glass. I tell him about teaching his pamphlet, Holding Vigil, which describes how he spent the day of May 19, 2021, as the state of Texas executed his friend, Quintin “GQ” Jones. Rickey lives on death row at the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, Texas. Holding vigil is what he does when there’s nothing else to be done. For GQ, and for every person taken from Polunsky to the death chamber in Huntsville, Texas, Rickey holds vigil in part by tapping a hairbrush on the tiny barred back window of his cell, which faces the courtyard where men are loaded into a transport van. Rickey has organized others on his cellblock in the tapping, so that what people hear as they are taken away are the sounds of solidarity. “The gesture is small,” Rickey writes, “but if I was in his shoes, I’d want somebody doing the same for me. If nothing else, it would boost my morale some, and show the guards that my (his) life matters to somebody here.”[xviii]

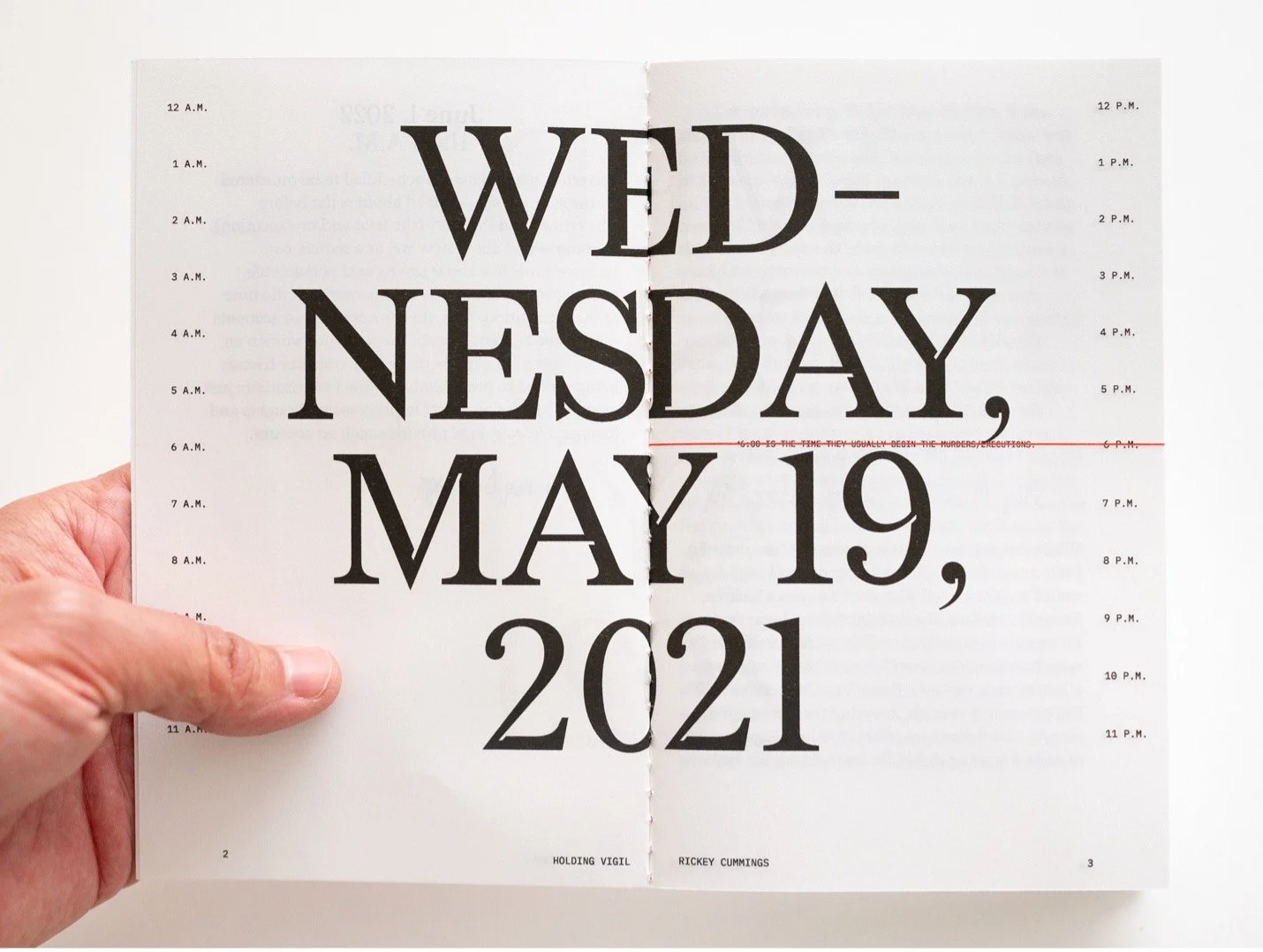

Image description: A hand holds a small white pamphlet with black text reading “Wednesday, May 19, 2021.” There are hour marks running alongside the left- and right-hand margins, and a red line running across the 6pm hour mark, which is the time that executions begin in Texas. Image credit: Mark Menjívar, used with permission of the artist.

The tapping is a poem. It cannot stop the mechanisms of state violence, but it is a means of holding space. Of holding vigil. And it asks something of us, too. A revolutionary awareness and demand.

I think with my students about the time of abolition, and about Rickey’s practice of holding vigil within this. Sociologist Avery Gordon describes the time of abolition as at once urgent and (often) unbearably slow and ongoing. As Gordon notes, “Abolition recognizes that transformative time doesn’t always stop the world, as if in an absolute break between now and then, but it is a daily part of it, a way of being in the ongoing work of emancipation, a work which inevitably must take place while you’re still enslaved, imprisoned, indebted, occupied, walled in, commodified, etc.”[xix]

I send this essay in progress to Rickey and he reminds me that the slave songs were also poems, and they were ways of getting free.[xx]

8. In the final pages of her book Carceral Capitalism, poet and scholar Jackie Wang describes the challenge of conveying, as a poet, “the message of police and prison abolition.” She writes, “I know that as a poet, it is not my job to win you over with a persuasive argument, but to impart to you a vibrational experience that is capable of awakening your desire for another world.” She goes on: “Our bodies are not closed loops. We hold each other and keep each other in time by marching, singing, embracing, breathing. We synchronize our tempos so we can find a rhythm through which the urge to live can be expressed, collectively. And in this way, we set the world into motion. In this way, poets become timekeepers of the revolution.”[xxi]

At the end of the semester, students talk about feeling “held” in the space of the class, in the community we made. This matters a great deal to me, of course. We made a community twice a week. We made it without punitive attendance requirements or firm deadlines or grades. And we made it in solidarity with Felix and Ray, with Rickey, with Akeil and Mark and Sam and Starr and Tamika and Paulette. We made it, as in poesis or making; poetics of abolition being a process, a daily making, a movement, at once urgent and ongoing.

I try not to get the students confused about this work, or to confuse myself. What we do in the classroom is not a march, and it’s not revolution, though we—the we of the classroom, which is not coextensive with the “we” of the institution—may also want that. But I think it is a way of holding vigil, of learning and preparing, of moving and breathing together, so that we can not just imagine but begin to set a different world in motion.

[i] Fred Moten, “the abolition of art, the abolition of freedom, the abolition of you and me,” perennial fashion presence falling (Seattle and New York: Wave Books, 2023), 58.

[ii] My thanks to Emma Schwartz, Charles Boyd, Felix (Phil) Rosado, Rickey Cummings, Stephanie Keene, Sonya Posmentier, Alicia Christoff, and Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb for ongoing conversations and contributions to the syllabus for “Poetics of Abolition.”

[iii] Audre Lorde, “Poetry is Not a Luxury,” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984), 37.

[iv] Ibid 38.

[v] Sylvia Wynter and Katherine McKittrick, “Unparalleled Catastrophe for our Species?: Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future: Conversations,” Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, ed. Katherine McKittrick (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2015), 24. See also Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Rehearsals for Living (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022), 19.

[vi] Joy James, “Airbrushing Revolution for the Sake of Abolition,” Black Perspectives (July 20, 2020), https://www.aaihs.org/airbrushing-revolution-for-the-sake-of-abolition/.

[vii] Joy James, Felicia Denaud, and Devyn Springer, “The Plurality of Abolitionism,” Groundings Podcast (January 1, 2021).

[viii] See, for example, bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York: Routledge, 1994); June Jordan, “The Creative Spirit: Children’s Literature,” Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines, ed. Gumbs, Martens, and Williams (Toronto: PM Press, 2016): 11-18; June Jordan, “Where is the Love?,” Some of Us Did Not Die: New and Selected Essays (New York: Basic Books, 2002): 268-274; Joy James, In Pursuit of Revolutionary Love: Precarity, Power, Communities (Brussels: Divided Publishing, 2022).

[ix] Luis Rodriguez, “On Poetry,” The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison, Ed. Caits Meissner (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022), 4.

[x] Etheridge Knight, “The Idea of Ancestry,” The Essential Etheridge Knight (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1986), 12.

[xi] Terrance Hayes, To Float in the Space Between: A Life and Work in Conversation with the Life and Work of Etheridge Knight (Seattle: Wave Books, 2018), 3.

[xii] My thanks to Felix (Phil) Rosado, Ray Tucker, Charles Boyd, and members of Let’s Circle Up at SCI Graterford and SCI Phoenix for their transformative facilitating, from which I have learned so much.

[xiii] Jordan Scott, Lanterns at Guantanamo, SFU Writers in Residence Chapbook Series, Simon Fraser University Department of English (2017), 17-18. http://lanternsatguantanamo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Lanterns-at-Guantánamo.pdf.

[xiv] See Kevin Quashie, Black Aliveness, Or A Poetics of Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021); see Sonya Posmentier’s forthcoming work on the Freedom Schools in Black Reading.

[xv] Assata Shakur, Assata: An Autobiography (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1987), 1.

[xvi] Ibid 59.

[xvii] James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (New York: Vintage Books, 1993 [1962]), 95.

[xviii] Rickey Cummings, Holding Vigil (Thick Press, 2022). To support Rickey Cummings, please visit http://iamrickeycummings.com.

[xix] Avery Gordon, “Some Thoughts on Haunting and Futurity,” Borderlands 10. 2 (October 2011). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A276187005/AONE?u=have19984&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=eeeea916.

[xx] My thanks to Rickey Cummings for his intellectual camaraderie and enormous generosity of mind and spirit.

[xxi] Jackie Wang, Carceral Capitalism (South Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2018), 319.

**********************************************************************

Lindsay Reckson is a scholar of post-Reconstruction literature and culture, working at the intersection of American and African-American literary studies, performance studies, media studies, and religion. Before coming to Haverford, Reckson was a Presidential Excellence Postdoctoral Fellow in English at the University of Texas at Austin. She has co-curated two exhibits, The Legacy of Lynching (2018) and Currently (2023), at Haverford's Cantor-Fitzgerald Gallery. Reckson is the author of Realist Ecstasy: Religion, Race, and Performance in American Literature (NYU Press 2020), and the editor of American Literature in Transition: 1876-1910 (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Institutional Context: Haverford College is a small, highly selective liberal arts college outside Philadelphia. Students who attend Haverford tend to be young people interested in social justice and creating meaningful transformations in the world. One of the benefits of Haverford's small size is close faculty-student collaboration and opportunities to experiment with innovative pedagogy.

Snapshot Institutional Profile* The IPEDs database we have used for other profiles in this project was malfunctioning at the time this post was uploaded. This data will be updated in the days and weeks to come.

**********************************************************************

This entry is part of a Public Writing Project, Higher Education for the World We Need, co-edited by Eric Hartman, Shorna Allred, Jackline Oluoch-Aridi, Marisol Morales, and Ariana Huberman. Initial reflections in that writing project will be posted here, on the blog of the Community-based Global Learning Collaborative (The Collaborative). The Collaborative is a multi-institutional community of practice, network, and movement hosted in the Haverford College Center for Peace and Global Citizenship. The Collaborative advances ethical, critical, aspirationally decolonial community-based learning and research for more just, inclusive, sustainable communities.